Being a woman in the 21st century brings with it many challenges and obstacles. Although the position of women socially, politically and economically has improved a lot over the years, most still do not feel safe in many situations involving men.

Surveys conducted as part of the #MeToo movement show that 77% of women have experienced verbal sexual harassment (cat calling), and as many as 51% of women have experienced unwanted touching with a sexual connotation.

The most common places where such incidents take place are streets, city buses, bus stops, unlit parks, construction sites, subways, trains, etc. Such devastating data have led some countries to try to find solidarity solutions. One of those attempts, which we will talk about here, is the Japanese trains in which only women can ride.

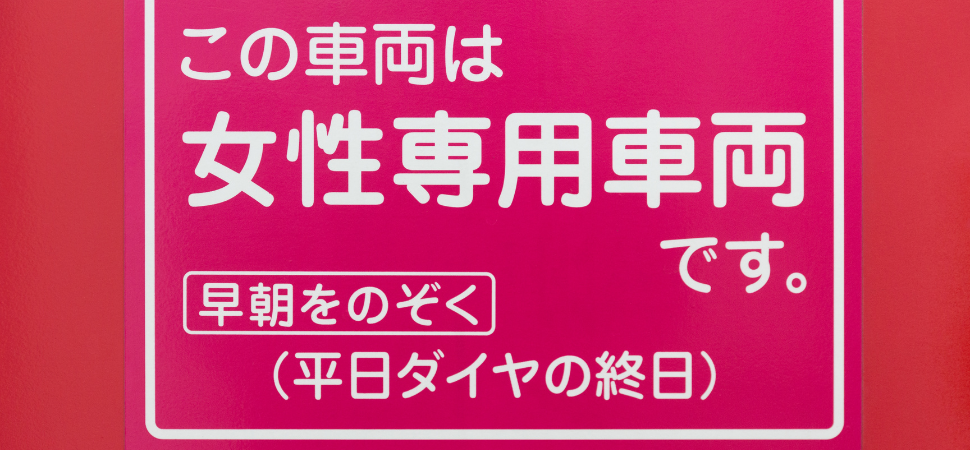

In Japan, women-only carriages were introduced as a form of combat against indecent behavior, especially indecent touching of women in the means of public transportation (Japanese: chikan). This "trend" in overcrowded trains is a major problem in Japan: According to the National Police Agency and the Ministry of Justice, the number of reported subway assaults in Japan between 2005 and 2014 ranged from 283 to 497 cases per year. Police and rail companies responded by putting up awareness posters and threatening stiffer penalties, but the trend continued.

Keio Electric Railway is the first company to take the next step after too many reports of this behavior during bōnenkai parties. The project "carriages only for women" started for a trial period and such trains were active only in the evening. However, a year after the introduction of women-only trains, the company introduced regular departures of these carriages that quickly became a standard practice.

However, the question arises, is something like this the only solution that exists?

Are women the ones who should have special sections of the train to ride in? These decisions of railway companies were initially met with positive reactions from users of public transport. Women got a safer space to get from point A to point B, and men avoided the chance of being falsely accused of touching someone inappropriately.

What started to go wrong in the meantime?

A lava of criticism started from male and female passengers because the regular carriages were overcrowded. Then, women began to use the women-only carriages less and less because they are either at the very end of the train and therefore impractical, or “they are full of people in heels who fall onto you if you stand next to them because they don't have the stability of someone in flat shoes”.

My conclusion regarding this topic can be read, or should be read as a criticism of the society we live in, in which Japan, although an economically advanced country, is no exception. For the fact that a woman is assaulted, there is no one else to blame but the attacker. However, the narrative that is constantly being pushed is the one in which the attacker is depersonalized, while the woman continues to be portrayed as weak, unprotected and in danger. If we started to frame our sentences as "men in Japan often sexually harass" instead of "women in Japan are often the victims of sexual harassment", I think we would solve the problem of depersonalizing the attackers, but at the same time it would become quite clear who should have received a special train carriage. Not the victims, but the attackers.

Some of the women's comments were that by going to the women's train, she would feel called out followed with a comment "you are not beautiful enough for anyone to touch you anyway". Precisely because of this, public social segregation should be directed towards the man who is the very cause of the problem at hand, and not the woman.